To teachers starting Mission 12 to ISS, this challenge was posted on Wednesday, September 13, 2017. It is designed to help you get your students immersed in Mission 12 microgravity experiment design by first exploring with them the concept of microgravity (the technical term for the phenomenon of ‘weightlessness’). As promised, here is the solution to the Challenge.

Note: the science content in this solution to the challenge was covered in detail during the 1.75 hour professional development Skype supporting Mission 12 program start, which was made available to each Mission 12 community’s Local Team of educators. These Skypes were conducted by SSEP Program creator and Director Dr. Jeff Goldstein through last week. One core objective of the Skype was to model best teaching practices to help teachers introduce the curricular story arc to their students in class. Dr. Goldstein covered topics from ‘what is microgravity’, to ‘why are the astronauts weightless’, to how to think about designing a microgravity experiment. The story arc, including this challenge and its solution, are part of the Designing the Flight Experiment page, identified during the Skype as critically important for all Mission 12 teachers and students. Designing the Flight Experiment is a subpage of the Teacher Resources main page, accessed in the navigation banner above.

Ok, I know you’ve been perplexed, and hanging out on the edge of your seat for the last few days. You’ve been patiently waiting for me to read my bathroom scale on top of my 260 mile high mountain that apparently even the U.S. Geological Survey knows nothing about (I checked at their website.) Wait! You say you have no clue what I’m talking about? Hey, you’ve got to read the original challenge FIRST! None of this lazy stuff going right to the answer.

Go read the original challenge, think about it for a while, and come back. I’ll wait right here for you. (Is that Jeopardy music playing in the background?)

And now the answer—

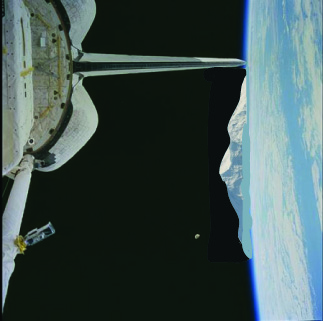

So I go to the top of my 260 mile (420 km) high mountain, and look … here comes the International Space Station … and there it goes! Man, it was moving fast. It was cruising at a whopping 4.7 miles PER SECOND (7.6 km/s)! Just 2 seconds ago it was heading right for me but was 4.7 miles away. A second ago it flew right by my face, and I looked in the window really really fast. And now it’s 4.7 miles away, heading away from me really fast.

Sure enough, when I looked inside, the astronauts were weightless—just floating around like there’s no gravity. So then I looked down at my bathroom scale, also expecting to be weightless—after all I’m at the same place they were. BUT WAIT!! My scale says I weigh nearly the same as my weight in my bathroom at home. More precisely, on top of my mountain I weigh 90% of my weight at sea level! So if I weigh 150 lbs at sea level, I weigh 135 lbs on my mountain. (Hmmm, wonder if I’ve discovered a new way to diet.) And I bet some of you won’t buy this without seeing the calculations. That’s good. That’s being a great scientist. (Keep reading.)

Metric system note: in the metric system, which is the system of units used by researchers and in science classrooms, weight is measured in Newtons (N). 150 lbs is equivalent to 667 Newtons (N). At the top of my mountain I’d weigh 90% of my surface weight, so I’d weigh 600 N.

But this can’t be right! Why are the astronauts weightless?

Lots of folks assume that a weightless astronaut means that gravity is somehow turned off in space. But you don’t need to think about this long to realize that’s a big-time misconception. Gravity is keeping the Space Station in orbit around the Earth, the Moon in orbit around the Earth, and the Earth in orbit around the Sun. If we suddenly turned gravity off, the Earth would fly out of its orbit, off in a straight line, and head out into cold, deep space. Gravity in space … GOOD. No gravity … BAD.

First some gravity basics. The force of gravity exists between any two masses, e.g., you and your computer, or your car and the building it’s parked next to. But as forces of nature go it’s a really weak force. So for you to easily see it in action, at least one of the masses needs to be really massive. A good example is the force of gravity between YOU and the EARTH. The Earth is pretty massive, and the force exerted on you by the entire Earth is what we call YOUR WEIGHT. Let’s think about this for a moment. When you jump up, nobody reaches up, grabs you by the ankle and pulls you back down to Earth. There’s this totally unseen force exerted on you by your planet that pulls you back down. You might have even heard the expression that you’re ‘falling under your own weight”, which is, well, what’s happening.

The force between two masses also depends on the distance between them. If you increase the distance between two masses, the force of gravity decreases. This comes together mathematically in the LAW OF UNIVERSAL GRAVITATION, a cool and pretty simple equation courtesy of Mr. Isaac Newton.

Ok, now let’s apply this. In the case of you and Earth, the distance between you and Earth is actually the distance between you and the center of Earth. But that distance is just the radius of Earth, or 3,963 miles (6,378 km.) When I go from sea level to the top of my really tall mountain, 260 miles (420 km) high, I’m increasing the distance between me and the center of Earth only a little bit. So my weight only goes down to 90% of its value at sea level. I actually used Mr. Newton’s equation to calculate my weight on top of my mountain. For those of you that want to see the calculation, I wrote it in my scratchy long-hand HERE. (Note my calculation shows more precisely that on the mountain I weigh 88% of what I weigh on the surface of the Earth. I’ll round that to 90% since the space station orbit can also be a little lower than 260 miles altitude).

Here’s another thing to ponder. The International Space Station (ISS) is pretty massive compared to you, and when it goes into orbit at 260 miles altitude, the force of gravity the Earth exerts on it – its weight – is also 90% of its weight at sea level. The weight of an astronaut is also therefore 90% of his/her weight at sea level. THEY ARE NOT WEIGHTLESS. The term WEIGHTLESS leads to a deep misconception. They only APPEAR weightless. Big difference. Again, your weight is the force of gravity exerted on you by the Earth. There is NO question that such a force is exerted by Earth on both the Space Station and the astronauts inside.

But why do they APPEAR weightless as if somehow gravity is magically turned off for them, or another way to say it – why are they just floating around inside the Space Station? Well in my case, I’m standing on top of my mountain, where the mountain is holding me up and keeping me from falling under the action of gravity. The mountain’s sayin’ “Hey! You’re not goin’ anywhere!” Gravity is pulling me down with a force defined as my weight, and the mountain is reacting under that ‘load’ with an equal and opposite force pushing me up. So for me, I actually experience two forces: gravity pulling me down, and the mountain pushing me up. The forces cancel each other, so my body isn’t literally forced to go somewhere else, and I just stand there at 90% of my sea level weight. I know my weight because when I step on my bathroom scale, my weight presses down on the scale, and the mountain pushes up on the scale so the spring in my scale is being compressed between the two forces, which causes the scale to show my weight. My bones also feel the resulting compression, which lets my body know that my bones are doing a good thing and are useful to keep (not the case in orbit where my body senses no bone compression, therefore thinks bones serve no useful purpose, and bone calcium is excreted. Yikes!)

But the Space Station is not resting on a mountain or anything else. The Space Station is ONLY experiencing the force of gravity. When that happens we call the situation free fall. The International Space Station is falling!! This seems contrary to the way most of us think about falling objects, where an object that is falling is getting closer to the Earth. But that too is a misconception. The Space Station is only experiencing the force of gravity, it is therefore falling – and it is moving around the Earth! Here’s something I wrote for a grade 5-8 lesson on free fall (See the “To Community Leaders and Teachers” section below), and it explains how you can be falling around the Earth.

Now back to the idea of weightlessness. Here is an analogy to help you understand. You’re in an elevator in a tall building. The elevator is on the top floor, not moving, and the elevator has no windows. Inside the elevator you’re standing on your bathroom scale. You note the scale reads your correct weight plus a couple of pounds ’cause you just finished lunch at the very cool top floor restaurant. Two forces are acting on you—gravity pulling you down, and thankfully the floor of the elevator pushing you up. Now (sorry) I cut the elevator cable. You feel that in your stomach? You’re now in free fall, with the force of gravity causing you to accelerate, which means your speed is increasing. You’re falling because I removed the ability of the elevator’s floor to push you back. And here is the key – the floor of the elevator is also falling with the exact same acceleration as you. The floor is falling WITH you. And the bathroom scale between your feet and the floor? Well, it’s also falling WITH you! There is now no way for the spring in the scale to be compressed between your feet and the floor … because the floor isn’t going to be pushing back. Look at the scale … it reads ZERO. You are weightless!

What? …. that’s not convincing you? Hmmmm……

Oooh oooh! Got it! Here’s another way to think about the elevator! Ok, imagine you’re back at the top floor and inside the elevator you are standing on a small chair, which puts you 1 foot above the floor. You decide to walk off the edge of the chair. But at the moment you walk off the chair you hit a button on the wall that detaches the cable holding the elevator, and the elevator and you plummet downward together, accelerating under the action of gravity. Now you are accelerating in the direction of the elevator’s floor BUT the elevator’s floor is accelerating in that same direction, which is away from you. You’ve stepped off the chair, but you never get any closer to the floor! What do you see as a passenger inside the windowless elevator? You’re not aware of anything moving. Inside the elevator, you are floating a foot above the floor – you are weightless, and in that elevator it APPEARS as if gravity is turned completely off. The obvious irony is that it is the force of gravity exerted by planet Earth on the elevator, me, the bathroom scale, and the chair that is causing us all to accelerate together, yet inside that environment, it’s as if gravity has been turned completely off.

Ok, just stopped you with the emergency brakes.

So here is the deal. If you are inside something freely falling (in free fall) like an elevator or a Space Station, you appear weightless. That’s because everything inside is falling with you, including the floor, walls, and ceiling—though calling them floor, walls, and ceiling is now rather meaningless.

A note to the deep thinkers (those that want to say “but Dr. Jeff you’re wrong.”) Yes, if the object is falling inside Earth’s atmosphere (like our elevator), it is technically not in free fall very long since the drag caused by the air soon becomes a force that needs to be considered. For instance, if you jump out of a plane, you’re in free fall in the very beginning of the jump, but the drag force from the air you are falling through increases as your speed increases. Soon you get up to about 100 mph (160 km/hr) and you won’t go any faster because the force of gravity down is balanced by the drag force up due to the air. You are said to reach a ‘terminal velocity’. But that’s still a bit too fast for a landing, so you open a parachute to dramatically increase the drag from the air, and you live to jump another day.

So for the elevator to truly be in free fall, let’s be more accurate by removing all the air from the elevator shaft, and also make sure the elevator is not rubbing against the walls of the shaft. Now gravity will be the only force acting on the elevator and everything inside it will experience weightlessness. And for the Space Station, well it’s in OUTER SPACE (say it with an echo for effect), and above the atmosphere, at least 99.999% of the atmosphere, and it is therefore truly freely falling – but moving around the Earth. That’s how I can read 90% of my weight standing on the mountain, and still see “weightless” astronauts inside the Station as it flies by the top of my mountain.

The Connection to Microgravity Experiment Design

So what does all this have to do with you designing a real microgravity experiment? The freely falling International Space Station serves as a laboratory for microgravity research. It is one of the main reasons it was built. What that means is that if we bring your experiment in your mini-laboratory to ISS (say a physical, chemical, or biological system you’d like to study), it will behave as if gravity is turned off. If you conduct the same experiment at the same time on Earth in gravity – called your ‘control’ or ‘ground truth’ experiment – then once your flight experiment is returned to you, a formal comparison of both will allow you to assess the role of gravity in the system you are studying. And what you’d like to study … is up to you! You and your team are the microgravity researchers here, so find a system to study that you find interesting. And there are lots of disciplines you can explore, like seed germination, crystal growth, micro-encapsulation, chemical processes, physiology and life cycles of microorganisms (e.g. bacteria), cell biology and growth, food studies, and studies of micro-aquatic life. Your teacher will provide you an understanding of these science disciplines over the next few weeks, which is all covered in the curriculum in the Document Library. So the essential question driving experiment design is …

What physical, chemical, or biological system would I like to explore with gravity seemingly turned off for a period of time, as a means of assessing the role of gravity in that system?

For your next stop on this journey in real science and real spaceflight, go check out the Designing the Flight Experiment page.

Good luck to all SSEP Mission 12 to ISS student microgravity researchers!

To Community Leaders and Teachers

We developed a great grade 5-8 lesson which easily demonstrates that astronauts inside a free falling soda bottle space shuttle appear weightless. The lesson is part of the Building a Permanent Human Presence in Space compendium of lessons for the Center’s Journey through the Universe program. The lesson is titled Grade 5-8 Unit, Lesson 1: Weightlessness, which can be downloaded as a PDF from the Building a Permanent Human Presence in Space page. You can also read an overview of the lesson conducted as part of one of the many Journey through the Universe Educator Workshops, this one in Muncie Indiana.

Photo credit: NASA (there was no mountain in their photo — promise. I’m getting good at photoshop.)

The Student Spaceflight Experiments Program (SSEP) is a program of the National Center for Earth and Space Science Education (NCESSE) in the U.S., and the Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Space Education internationally. It is enabled through a strategic partnership with DreamUp PBC and NanoRacks LLC, which are working with NASA under a Space Act Agreement as part of the utilization of the International Space Station as a National Laboratory. SSEP is the first pre-college STEM education program that is both a U.S. national initiative and implemented as an on-orbit commercial space venture.

The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Center for the Advancement of Science in Space (CASIS), and Subaru of America, Inc., are U.S. National Partners on the Student Spaceflight Experiments Program. Magellan Aerospace is a Canadian National Partner on the Student Spaceflight Experiments Program.